“He restores my soul. He leads me on paths of righteousness for His name’s sake.

Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death,

I will fear no evil, for you are with me; your rod and your staff, they comfort me.”

Psalm 23:3-4

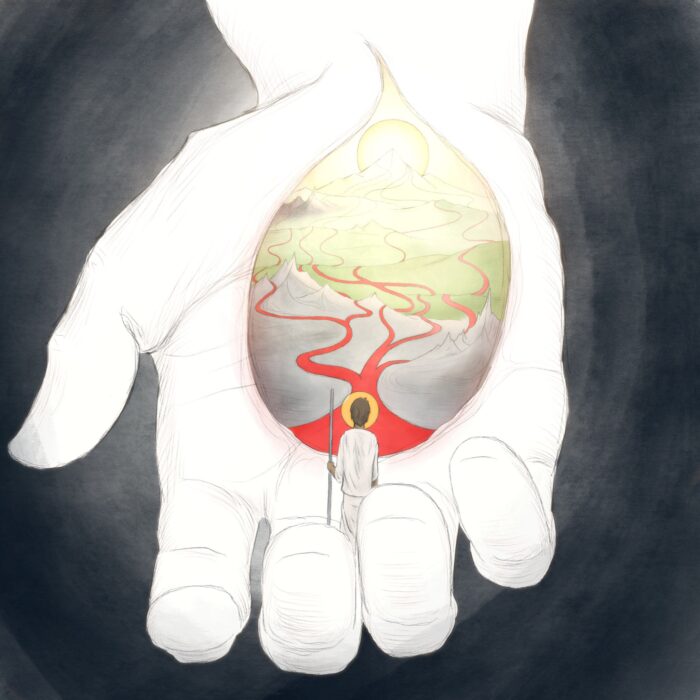

I wanted this image to visually express the transition from the pastures into the valley that takes place between verses 2 and 4. The overall color scheme is much darker and the jagged edges of the valley frame the distant pastures in the background.

Verse 3 emphasizes the sovereign leading of the shepherd. It is he who guides and goes before His sheep. This is significant to note because in verse 4 we find ourselves in the Valley of the Shadow of Death. The implication is that the sheep is in the valley because the Shepherd has led him there. And—because the entrance into the valley of shadow is by the design of the Good Shepherd—I wanted to show that the sheep is no less in the almighty hand of his shepherd in verse 4 than he was in verses 1-3. In fact, the sheep’s intimacy and dependency upon the shepherd is only intensified by the valley. In the pastures the shepherd’s presence and goodness were mediated by the grass and water, but in the valley the mediators have been removed and the shepherd himself has become the desperate and hope-filled focus of the lamb (“I will fear no evil for you are with me.”).

The attacking wolf represents the onset of the valley and its terrors (It need not be only death. The Hebrew word translated “shadow of death” can apply to various grievous and hard to bear sufferings that come as we live life in a fallen world. Sickness, loss, a season of doubt or darkness in the soul might all be categorized under this shadow). The shepherd’s hand on the wolf’s head is intentionally ambiguous. He could either crush the animal’s skull into the ground….or allow it to continue its trajectory toward the lamb. However—whatever the outcome— the hand on the wolf’s head declares the shepherd’s sovereignty over all that befalls his own (John 10:28, 21:19, 22).

The wounds of the shepherd visible behind the head of both the lamb and the wolf declare two different truths. The wound behind the head of the wolf reminds us that Christ’s death and resurrection has overcome all of His people’s enemies and that—should they be allowed to harm His beloved—it will only be to the enemy’s final downfall and His people’s exaltation (John 16:33, Philippians 1:28-29, 2 Thessalonians 1:5-8, Revelation 12:11).

The wound behind the lamb’s head is a reminder that our Lord and God and Shepherd Himself has suffered equivalent to and greater than any suffering He may ordain for us. The hand wounded in sovereign love authors our sorrows, and because He Himself is a slain yet living Lamb, He has infinite compassion on those whom He leads. The shepherd who laid down his life as a lamb is the one who goes before us (Isaiah 49:10, Micah 2:12-13, John 10:4, Hebrews 2:18, Revelation 7:17). And since he has led the way through suffering into glory, He has transformed all of our suffering into an avenue for deeper fellowship with Him, fuller joy in Him, and greater exaltation of Him (2 Corinthians 12:9, Philippians 3:10, 1 Peter 2:21).

Notice also that, if the wolf is to attack the lamb, it must pass the through the cross (represented in the staff). This is yet another reminder that the death and resurrection of our Good Shepherd has “de-fanged” the enemy. Because of Christ’s victory on Calvary, tribulation, distress, persecution, famine, nakedness, danger, sword—and whatever else might assail the people of God—cannot separate us from the love of God and, indeed, can only serve our ultimate good and His ultimate glory (Romans 8:28. 31-39).

Lastly for verse 4, I wanted to really emphasize the intimate fellowship with the Savior that often comes in the context of suffering (though it might not feel like it in the moment). First, notice that the lamb is intently focused on the shepherd and that the shepherd’s head is inclined toward the lamb. Though the wolf is slathering and raging, it is not the focus, rather, its onslaught has driven the sheep closer to the master. Second, the light of the two halos forms a sort of quiet, personal space—shared by the sheep and shepherd—amidst the darkness and motion in the rest of the image. And lastly, notice that the distant green pastures and still waters are visible through the face and torso of the Shepherd. The soul-restoring kindness of the shepherd, previously mediated through grass and water, is now accessed directly—and only—through communion with the Shepherd Himself.

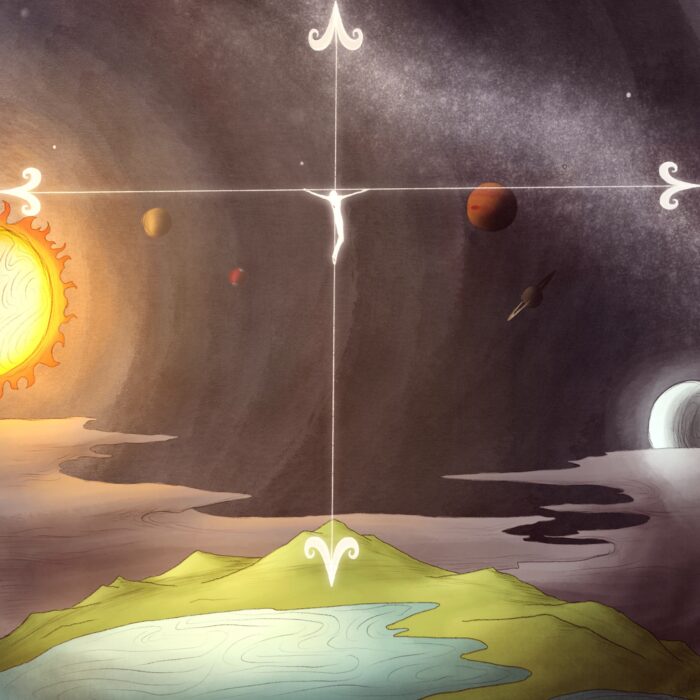

In conclusion, I want to point back to verse 3. There we read that YHWH leads His people in paths of righteousness for His Name’s sake. There is much to say about that statement, but for this image the main thing I tried to emphasize is that the paths into which YHWH sovereignly leads His own are intended to make the goodness and beauty of His Name known to them and to those who observe their lives. This is true even (and especially) of those paths that lead through dark valleys because the Name of YHWH is most perfectly communicated in the death and resurrection of Christ, and when the Christ-follower is led through a time of hardship, the glory of Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection is—in a sense—echoed in their lives.

Christ’s love-borne death reverberates in His people’s sufferings as they entrust themselves humbly into the hand of God to do with them what He will for His glory (1 Peter 2:19-21). And the joy of Christ’s resurrection radiates from His Bride’s face as she endures hardship with hopes set, not on the things that are seen, but on the unseen, blood-bought, and resurrection-assured glory that is to come (2 Corinthians 4:14-18).

So, by making the practical implications of Christ’s death and resurrection visually apparent in this image, I am attempting to show that the valley experiences of God’s people bring the crucifixion and resurrection to the foreground and, consequently, glorify the name of our Shepherd and God who is climactically declared at the cross (Psalm 23:3, John 17:26).