John 20:19-20,”Jesus came and stood among them and said to them, ‘Peace be with you.’ When He had said this He showed them His hands and His side. Then the disciples were glad when they saw the Lord.”

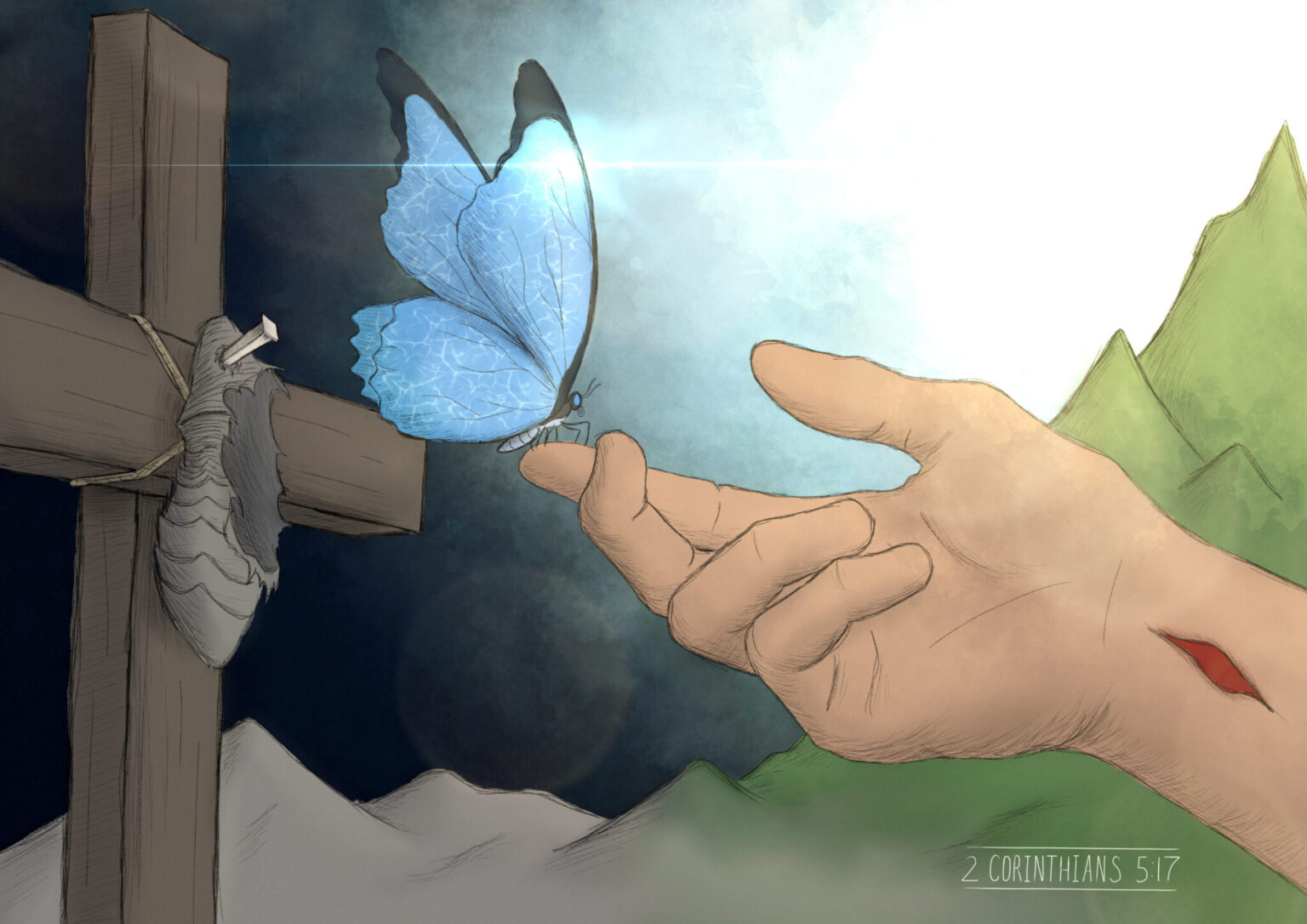

The Resurrected Jesus Christ still has wounds in His hands.

Even though His eternal body is healed from the torments of His death, even though it is new and incorruptible – invincible to entropy – even though it is the body in which He now reigns over reality, He still carries wounds in His hands, and side (and, presumably, His feet as well). Consider the wonder of that fact, the one in whom we will eternally know God, the Beauty of the Beatific Vision – is and ever will be wounded.

Why? Why were these five wounds not healed with the rest of His body? That is the question I want to address in this and the next few blog posts leading up to Good Friday. There are, no doubt, many reasons why God has ordained that Christ’s wounds be eternal, but I want to look at just a few over the next week, the first being that the eternal wounds of Christ declare God’s total victory over suffering and sin.

God could make us forget suffering and sin. However, If He were to completely erase suffering from our minds and banish the memory of sin, then it would seem that He was incapable of redeeming them. It would seem that, in a sense, they had won because all God could do was cover them with a thick layer of blessing so that we would forget their horrors. But this is not God’s way.

Instead, He engraves an everlasting reminder of them into His own hands, so that whenever His people see Him in His eternal glory, they will also see the effects of sin’s most grievous blow. The greatest beauty will forever remind us of the greatest suffering. And yet, precisely because the reminder of suffering comes through beauty, it will also be a declaration of suffering’s final and utter defeat.

“There is the wound of sin. There is the wound of suffering. I am not forgetting they happened, I am staring them in the face, and still I rejoice with joy inexpressible at the glory and victory and beauty of my King, made all the more beautiful because of those wounds….those wounds that declare, ‘this was the worst sin could do to me, this was the worst suffering could do to me, and I have overcome.'”

And what does this mean for us, the people of the Wounded King? It means that our eternal joy does not depend on the hiding of this life’s horrors, but on the “beatification” of them.

The wounds of the glorified Christ cast a glory backward over His suffering in this life. So that – because we know the Wounded King now sits enthroned in total victory – His sufferings in Gethsemane and on Golgotha take on a peculiar and sacred beauty. In a similar way, our sufferings will be “sanctified” in eternity. Just as Christ’s deepest suffering is not forgotten, but turned to His glory, so too our darkest trials in this life will be made servants of our joy in the New Creation.

Perhaps a word-picture modified from one of JRR Tolkien’s works will help to solidify these thoughts:

Imagine a skilled street musician is playing his instrument when a trouble making young kid comes up and starts to bang pots and pans together to ruin the musician’s song. What makes the musician look more “glorious,” if he plays louder and eventually drowns out the boy, or if he smiles and plays a song that folds the boy’s cacophony into itself, become all the more beautiful for it?

This second scenario is what God has done with suffering and sin. The wounds of Christ are the declaration that evil’s most discordant “note” has been folded into the song of God’s glory and made its high point. And if this is the case for the greatest suffering, surely it will be the case for our own.